As you move through the galleries of the National Civil Rights Museum, you follow a timeline of struggle and strength. The sounds of freedom songs trail behind you as you step into Birmingham, Alabama – a town that became known as “Bombingham” and the center of the Civil Rights Movement. On a busy day, you might notice a life-size image of a young girl holding a sign: “Can a man love God and hate his brother?”

As you move through the galleries of the National Civil Rights Museum, you follow a timeline of struggle and strength. The sounds of freedom songs trail behind you as you step into Birmingham, Alabama – a town that became known as “Bombingham” and the center of the Civil Rights Movement. On a busy day, you might notice a life-size image of a young girl holding a sign: “Can a man love God and hate his brother?”

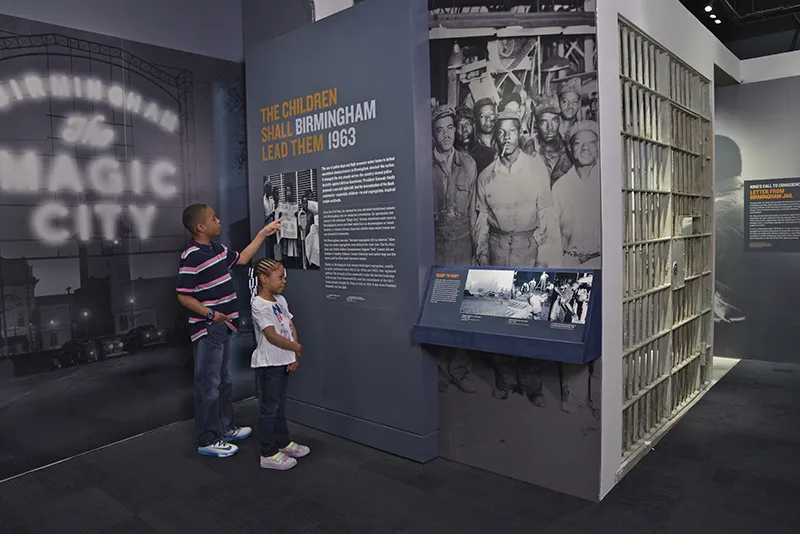

Your attention might be drawn to the replica jail cell and the voice of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. reading his “Letter from a Birmingham Jail.” Or perhaps one of the most striking images to me in the entire museum catches your eye – a woman in a dress and high heels being arrested the same day as Dr. King.

What you might miss, however, is the deeper story behind these images.

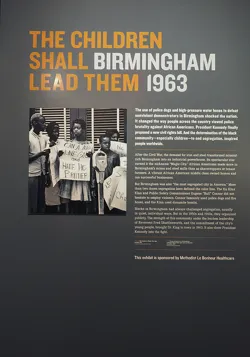

On May 2, 1963, over 1,000 students marched through downtown Birmingham in what would become known as the Children’s March. That morning, hundreds of the city’s students – the youngest, nine-year-old Audrey Faye Hendricks – gathered at the 16th Street Baptist Church. Audrey seemed destined to make history. Her parents were active in the NAACP until Alabama outlawed it and became early members of the Alabama Christian Movement for Human Rights (ACMHR). On May 2, Audrey was the only one of her classmates to join the marches.

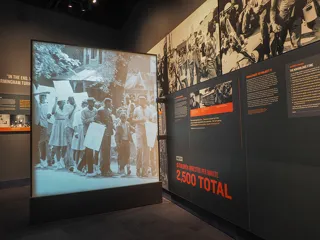

The students were arrested as they marched and were taken to the Birmingham City Jail by the hundreds, overwhelming the capacity of the jail. The next morning, hundreds more students gathered.

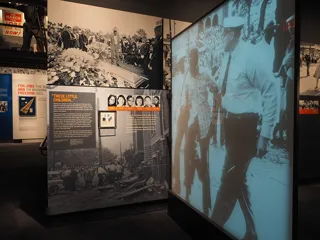

City Commissioner of Public Safety, Eugene “Bull” Connor, a staunch segregationist, ordered the police and fire departments to brutalize the children. The images captured that day changed the national conversation on the Civil Rights Movement. They sprayed fire hoses so forceful they ripped the bark off of trees and clothes off people. They sprayed children and teenagers until they were thrust against buildings and against cars. Officers used trained police dogs to intimidate and attack the protestors.

City Commissioner of Public Safety, Eugene “Bull” Connor, a staunch segregationist, ordered the police and fire departments to brutalize the children. The images captured that day changed the national conversation on the Civil Rights Movement. They sprayed fire hoses so forceful they ripped the bark off of trees and clothes off people. They sprayed children and teenagers until they were thrust against buildings and against cars. Officers used trained police dogs to intimidate and attack the protestors.

The protestors marched on anyway, singing “Ain’t Gonna Let Nobody Turn Me Around.” In the exhibition, a life-size screen showing these pictures standing in your way, asking you to consider them, and their meaning, before continuing on.

For days, children led the way in Birmingham. They faced fire hoses, biting dogs, and billy clubs. They faced imprisonment – Audrey Faye Hendricks stayed in jail for six days before her release. For the rest of May, the eyes of the world were on the students and their fight against injustice.

As you turn the corner to leave the Birmingham gallery, you might notice a floor-set TV with young visitors seated before it, watching in awe at both the technology itself and the disturbing images. Turn around and you’ll notice a smaller encasement, tucked away, displaying the faces of six black children – martyrs in the Movement for freedom.

As you turn the corner to leave the Birmingham gallery, you might notice a floor-set TV with young visitors seated before it, watching in awe at both the technology itself and the disturbing images. Turn around and you’ll notice a smaller encasement, tucked away, displaying the faces of six black children – martyrs in the Movement for freedom.

On September 15, 1963, white violence took their lives, four at 16th Street Baptist Church and two within hours of the church bombing, in the streets of Birmingham. Birmingham is a story of great sadness and great triumph. The internal fire of Birmingham’s children paved the way for the Civil Rights Act of 1964 that outlawed legal segregation in the United States. It showed, as Dr. King would later say, “there is a certain kind of fire that no water can put out.”