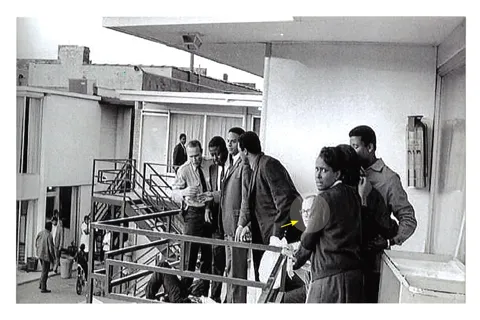

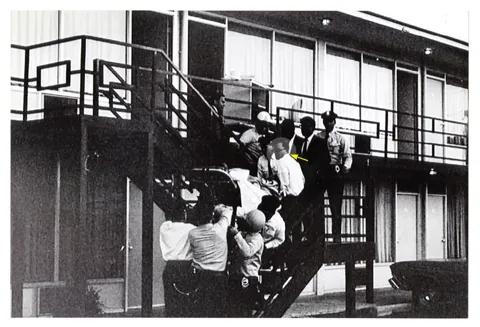

Photographs taken at the Lorraine Motel on April 4, 1968, have indelibly etched our museum’s landmark in America’s collective memory. These famous images were taken in the midst of the chaos that ensued after Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. was shot on the balcony outside Room 306. In the first photo, Shelby County Sherriff’s Deputy Bill DuFour is speaking with three of King’s most recognizable aides, Ralph Abernathy, Andrew Young, and Jesse Jackson, as they stare in disbelief at the body of Dr. King. Crouching on the floor near Dr. King is James H. Laue. Laue was one of two white guests staying at the Lorraine Motel that day. As a U.S. Department of Justice mediator, he had come to Memphis to help resolve the Sanitation Workers Strike and to lend support to Dr. King and his cause. Though not as well known as the activists in the photograph, Laue built an impressive legacy as an advocate for civil rights and peaceful conflict resolution.

James Laue was born in River Falls, Wisconsin, in 1937. After completing his undergraduate work at the University of Wisconsin, he attended Harvard University where he received both his master’s and Ph.D. As Laue studied sociology and race relations, he became increasingly involved in the Civil Rights Movement. While participating in lunch counter sit-ins and church “kneel-ins” and interacting with SCLC and SNCC members, Laue began to formulate an intellectual trajectory that would shape his life’s work. His doctoral dissertation topic at Harvard University was entitled, “Direct Action and De-segregation: Toward a Theory of the Rationalization of Protest.” In 1965, Laue joined the Community Relations Service, a division of the Department of Justice. His job as the Assistant Director of Community Analysis was to gather information on communities to see if there was potential for racial conflict. It was in this capacity that Laue was in Memphis on April 4th.

Laue was staying in Room 308, two doors away from Dr. King, and at 6pm, he had just turned on the television to watch the evening headlines when he heard what sounded like the pop of firecrackers in the courtyard below. Stepping on the balcony outside his room, he was stunned to see Dr. King on the floor, bleeding from a neck wound. He recalled rushing back to his room for towels and a blanket to make Dr. King comfortable. Laue also was the one who shared the shocking news with Ramsey Clark, U.S. Attorney General.

Laue was always reluctant to discuss this tragic event, and only wrote about his experience a few months before his death in September of 1993. Still, his relationship with Dr. King had a tremendous impact on Laue’s life. Reflecting on the eight years during which he worked with Dr. King, Laue said, “His life – and his death – changed my life. He taught me that ‘conflict resolution,’ a laudable goal on the surface, does not truly occur without struggle refined in love and that justice is not fulfilled without reconciliation.” By bearing witness to King’s achievements and also that moment of historic violence, Laue’s life was changed forever.

In the years after King’s death, Laue’s spiritual beliefs, combined with his activism, framed his academic trajectory and his life’s work. In 1979, President Jimmy Carter appointed Laue Chair of the Congressional Commission on Proposals for the National Academy of Peace and Conflict Resolution. The commission would eventually create the U.S. Institute of Peace. Also, Laue held positions at several prestigious institutions, including Harvard Medical School and Washington University in St. Louis. In 1986, he became the first Lynch Professor of Conflict Resolution at George Mason University in Virginia, an endowed chair position that he held until his death in 1993 at the age of 56.

In 2017, I had the privilege of meeting with Ron and Lisa, Laue’s children. They live in different parts of the United States and on different occasions had come to visit our museum with their families. Both Ron and Lisa remarked that their father never spoke about his experience of being at the Lorraine Motel on April 4, 1968. Despite his list of notable achievements, Laue has become an almost anonymous presence in the famous photographs taken just moments after King’s assassination.

Others have remembered his legacy of activism. In an eloquent condolence letter to Laue’s widow, Ramsey Clark wrote “Jim believed that to get a job done it’s better to encourage others and persevere, than to proclaim and self-promote. The deep respect Dr. King had for Jim, shared by the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, was based on Jim’s dependable, unadvertised performance. This is why Jim was at the Lorraine on the terrible day Dr. King was killed.” This seems in keeping with Laue’s unheralded presence in the tragic events of April 4th. Yet I have also learned that his appearance in these photos may be read as an important symbol of his life of activism that affected so many people.

I would like to thank the Laue family for donating James Laue’s typed memoir, “25 Years Ago: A Personal Report from Memphis,” and additional photographs to the National Civil Rights Museum. The photos of Dr. King’s assassination were taken by the late South African photographer, Joseph Louw. If you would like to donate an item to our collection, please contact me, Raka Nandi at rnandi@civilrightsmuseum.org.