by Ryan M. Jones, Associate Curator

Sixty years ago, the state of Mississippi was a hotbed for civil rights. It led the nation in racially motivated violence, and less than 3% of the black population was registered to vote. Following the events of the year 1963, in which Americans were horrified by witnessing the attacks on children marching nonviolently throughout the streets of Birmingham, the memorable March on Washington, and the assassinations of civil rights leader Medgar Evers and President John F. Kennedy, the movement was at its highest peak.

President Kennedy proposed a civil rights bill to Congress just months before his death, and his successor, Lyndon Johnson, committed to continuing Kennedy’s proposal and signing it in 1964. Other efforts were quietly planned.

Bob Moses, a civil rights activist, came to Mississippi in 1961 to begin voter registration drives across the state, which received expected backlash from segregationists. By 1964, things had not changed, and one could argue things got worse. Moses, Aaron Henry, and Dave Dennis, planned to bring thousands of college students into the state that summer to help register black voters and to establish Freedom Schools to teach Black history to Black youth.

The year was also an election year, and the all-white, all-male Mississippi Democratic Party was adamant about keeping Black representation out of the political process. Moses, Henry, and Dennis named the campaign “Freedom Summer.” The state of Mississippi referred to it as an “invasion.”

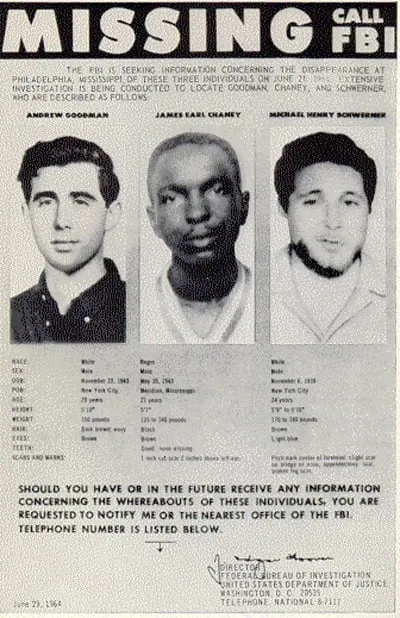

The Mississippi Freedom Project sought to bring college students, mostly white into the state to bring awareness to the disenfranchisement of Black Americans due to Mississippi’s deplorable discriminatory practices and policies. One of the early organizers was a white social worker from New York named Michael Schwerner. Schwerner, nicknamed “Mickey,” arrived in Meridian, Mississippi, in January and soon befriended a local active civil rights worker named James Chaney, who was black. The two men would help organize to help open Freedom Schools in the Meridian area and in Neshoba County, 30 miles to the west.

The White Knights of the Ku Klux Klan took notice of Schwerner, whom they referred to as “Goatee.” The Klan in the Meridian and Neshoba County klaverns despised Schwerner, and he was marked for death by the Imperial Wizard in May 1964. Thousands of Freedom Summer volunteers traveled to Oxford, Ohio to participate in a training course that would prepare them for their summer visit in Mississippi. They were given a sober lecture from Bob Moses, who informed them, “You could be heckled, you could be attacked, you could be arrested, and you also could be killed.”

Twenty-year-old Andrew Goodman, also a Caucasian from New York, heard this lecture. After watching the March on Washington the previous August, Goodman told his parents that he wanted to participate in the movement. When he saw flyers at his school, Queens College, he signed up and went to Ohio. There, he met Schwerner and Chaney.

The Klan went to one of the churches where Schwerner and Chaney were holding meetings in the town of Longdale. Once the Klansmen saw that Schwerner was not at the Mt. Zion Methodist Church, they beat members of the congregation and set the church on fire. This was a tactic to lure Schwerner back to the area for death. The tactic worked. Schwerner, Chaney, and now Goodman traveled back to Meridian to investigate what remained of the burned church. Goodman was not part of the original plan to return to Neshoba County, but he insisted.

On their way back to Meridian, they were spotted by Deputy Cecil Price and arrested. Chaney was charged with speeding, and Goodman and Schwerner were held for “investigation” as suspects of the Mt. Zion Church burning, which occurred when they were in Ohio. Deputy Price, a member of the Klan informed other Klansmen that they had “Goatee” and to assemble a plan. The three men were released around 10:30 pm and never seen alive again.

For the next 44 days, President Johnson ordered J. Edgar Hoover’s FBI to find the men. During the search, the bodies of several other African Americans were found in creeks, swamps, and rivers, though none were the bodies of the missing civil rights workers. On August 4, underneath 15 feet in the earthen dam called Old Jolly Farm, the bodies of Andy Goodman, James Chaney, and Mickey Schwerner were found. Autopsies showed that each man had been shot, and Chaney was brutally beaten. The FBI charged 17 Klansmen, including Deputy Cecil Price and the Imperial Wizard, Sam Bowers, with violations of civil rights, not murder. Seven men were ultimately convicted, and none served more than ten years in prison.

Sixty years later, the impact of the murders contributed significantly to the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, making segregation of public facilities unconstitutional. It was a catalyst for the Voting Rights Act of 1965, which would effectively outlaw discriminatory voting practices. The murder case also brought international media attention to the civil rights movement, largely because two of the victims were Caucasians who lived outside of the Deep South.

The incident strengthened civil rights organizations like the Congress of Racial Equality and the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, which had been working on voter registration and other civil rights campaigns in the South. Their deaths underscored the dangers faced by activists and increased solidarity and determination within the movement. The legal proceedings marked one of the very first successful prosecutions of civil rights murders in the South.

While seven men were ultimately convicted, none were ever charged with state murder charges until in 2005, exactly 41 years to the day when Edgar Ray Killen, the mastermind behind the conspiracy to lure, ambush, kill, and bury the bodies was convicted of manslaughter at the age of 80. At the time of his conviction, four Klansmen were still free men in Philadelphia, Mississippi who went unpunished.

The murders of James Chaney, Michael Schwerner, and Andrew Goodman were pivotal events that helped drive legislative changes and increased federal involvement, which further exposed a legacy of racism in American society and the relentless pursuit of racial equality.

The Mississippi Freedom Summer taught us that collective action can drive significant legislative and social changes even in the face of severe adversity and violence. The brutal murders of civil rights activists underscored the high cost of fighting for justice but also highlighted the importance of continued vigilance and courage in the face of oppression.

The involvement of white allies, such as Michael Schwerner and Andrew Goodman, demonstrated the strength and impact of allyship in social justice movements. Their sacrifice, alongside Black activists like James Chaney, showed that true progress often requires diverse coalitions and mutual support across racial lines. The burden to make lasting change has always laid heaviest on the perpetrators, not the victims, of injustice.

The events of Freedom Summer also emphasized the critical importance of voter turnout in elections. The effort to register Black voters and challenge discriminatory practices highlighted how voter suppression can undermine democracy and how empowering marginalized communities to vote can lead to systemic change. High voter turnout remains essential for ensuring that all voices are heard and represented in the political process.

Today, the lessons from Mississippi Freedom Summer resonate in ongoing struggles for civil rights and social justice. Additionally, ensuring high voter turnout remains a fundamental goal to protect and advance democratic values. Increasing voter turnout in an environment of misinformation, fearmongering, and division requires a multifaceted approach that addresses the root causes of apathy and distrust while promoting the importance of civic engagement.

This is the continued work for Americans who stand for true democracy. It is why the National Civil Rights Museum is dedicated to sharing the history of courageous Americans so that we preserve the blueprints of the frontlines laid before us by those who sacrificed so much.

Join the National Civil Rights Museum on July 27 for a symposium entitled, “Honoring the 60th Anniversary of Freedom Summer and the Civil Rights Act of 1964” where living legends of Mississippi Freedom Summer and today’s activists share their perspectives on how we move forward. Through their stories, we not only have strategies for future generations, but understand that NOW is the time for us to take up the mantle! We must encourage everyone to vote like our lives depend on it.