White columns guide you when entering the Brown vs Board of Education exhibition. On the right are pews and a short video recapping the world-changing U.S. Supreme Court decision on May 17, 1954, 66 years ago this week.

White columns guide you when entering the Brown vs Board of Education exhibition. On the right are pews and a short video recapping the world-changing U.S. Supreme Court decision on May 17, 1954, 66 years ago this week.

For 89 years, schools across the South were racially segregated and drastically different. Despite a court order stating “separate but equal” facilities were constitutional, inequity ran rampant in southern schools. The NAACP successfully argued that under the 14th Amendment’s equal protection clause, this system was detrimental to the success and psychology of Black youth. The success of Brown was the first legal win of the modern Civil Rights Movement and would pave the way for the successes to follow.

Left of the white marble entry is the story of what happened in southern classrooms. A touchscreen map of the United States shows school integration stories from 1835 to the late 1970s. Three desks line the wall, each housing artifacts from the post Brown twenty-five-year struggle to desegregate southern schools.

Left of the white marble entry is the story of what happened in southern classrooms. A touchscreen map of the United States shows school integration stories from 1835 to the late 1970s. Three desks line the wall, each housing artifacts from the post Brown twenty-five-year struggle to desegregate southern schools.

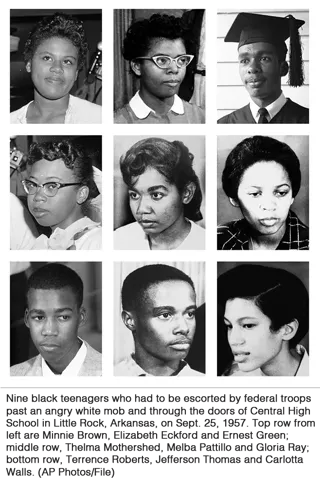

Three years after the Brown decision, nine African American teenagers braved white mobs to desegregate Central High School in Little Rock, Arkansas. You might be familiar with Melba Patillo Beals’ book, Warriors Don’t Cry, which chronicles her time at Central.

Central High School was one of the largest schools in Arkansas with approximately 2,000 white students enrolled. On September 4, a mob of over 1,000 angry white protestors and the Arkansas National Guard met the nine African American students. Governor Orval Faubus mobilized the Guard to prevent the students from entering the building. After several thwarted attempts and President Eisenhower’s intervention with the 101st Airborne, the students were attending classes by the end of September.

The students faced daily verbal and physical abuse by the white students. Beals recalls female students dropping burning paper on her in the restroom stall. Minnijean Brown, after responding to abuse in the school cafeteria, was suspended for the rest of the year.

The students faced daily verbal and physical abuse by the white students. Beals recalls female students dropping burning paper on her in the restroom stall. Minnijean Brown, after responding to abuse in the school cafeteria, was suspended for the rest of the year.

In the desks along the exhibition wall is a letter written to another of the Little Rock Nine, Ernest Green. Green was the only senior to enroll at Central High School that fall. After surviving the year, he had more than earned the right to walk and receive his diploma. Graduation is a rite of passage for students all across the country and, particularly for the Green family, a moment of triumph and celebration. In the letter, “a worried senior” expressed their concern over “trouble that will most probably arise” if Green attended the graduation ceremony.

The student continued, saying the ceremony “will be a time that I and hundreds of others do not wish to have marred…” and that Green should let “unselfishness” guide his decision. Despite this letter implying Green did not deserve an unmarred ceremony like the other seniors, he attended. His family, accompanied by Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., sat in the audience.

After graduation, Green earned a BA and an MA from Michigan State University and went on to a distinguished career in both the public and private sectors.

As seniors and graduates across the globe today mourn the preempting of their graduations, we reflect on the hard-fought battle for school integration and the sacrifices made by students like Ernest Green and the Little Rock Nine.