by Amy Nathan Wright

In May 1967, Dr. King announced to the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC), “We have moved from the era of civil rights to the era of human rights,” from a “reform movement,” into “an era of revolution.” In his final book, Where Do We Go from Here: Chaos or Community?, King described a multipronged approach to creating change that revolved around opposing the war in Vietnam, organizing workers through unions, mobilizing consumers through boycotts, and combatting poverty across racial lines. King declared that, “As we work to get rid of the economic strangulation that we face as a result of poverty, we must not overlook the fact that millions of Puerto Ricans, Mexican Americans, Indians, and Appalachian whites are also poverty-stricken.” The seeds for SCLC’s most concentrated and sustained effort to combat poverty—the 1968 Poor People’s Campaign—were sown. But King’s first-hand experiences in both rural and urban areas in the U.S had already informed a long-standing commitment to economic human rights.

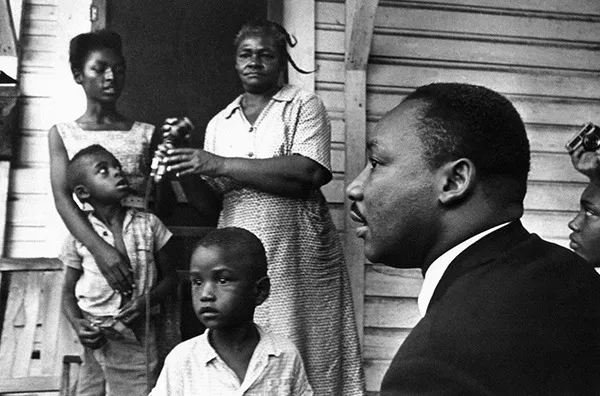

King's position on poverty and economic inequality, which was influenced by early childhood experiences, such as witnessing Great Depression-era soup lines and working on a Connecticut tobacco farm, was very much grounded in his devotion to the Christian concept of a “beloved community.” In an 1956 sermon, “Paul’s Letter to American Christians,” King proclaims, “God never intended for a group of people to live in superfluous inordinate wealth while others live in abject, deadening poverty. God intends for all of His children to have the basic necessities of life, and He has left in this universe enough and to spare for that purpose. So I call upon you to bridge the gulf between abject poverty and superfluous wealth.” King didn’t just preach an anti-poverty message; he bore witness to its devastating effects and encouraged others to do the same. From the Montgomery Bus Boycott to his assassination while working on the Memphis Sanitation Worker’s Strike just prior to the launch of the Poor People’s Campaign, King pursued the “dual agenda” of civil and economic rights. In his 1957 book, Stride Toward Freedom, King declared that while the nonviolent struggle would help “end the demoralization,” a “new frontal assault on poverty” would “make victory more certain.” Thomas R. Peake explains that during that summer he urged U.S. Vice President Richard M. Nixon and Secretary of Labor Secretary James P. Mitchell to travel throughout the South to witness the worsening poverty and to provide increased federal aid for the poor.

Even some of King’s landmark speeches include pointed critiques of capitalism and passionate calls to end poverty. In his 1963 “Letter from Birmingham Jail,” King decries that “the vast majority” of blacks were “smothering in an airtight cage of poverty in the midst of an affluent society.” And while the media typically strips the 1963 March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom and King’s “I Have a Dream” speech of their economic agendas, he clearly proclaims that “the Negro lives on a lonely island of poverty in the midst of a vast ocean of material prosperity,” and reminds his audience of the March’s purpose “to dramatize” this “appalling condition.” In his 1964 book, Why We Can’t Wait, King produces solutions, proposing “a broad-based and gigantic Bill of Rights for the Disadvantaged” patterned after the G.I. Bill, as well as full employment, a living wage, and a guaranteed income. King also called for creative solutions for “neutralizing the perils of automation,” demonstrating that he had a stronger grasp of the economy and its future than current politicians.

King’s personal commitment deepened during the summer of 1966 after spending months living in an urban slum and leading an anti-housing discrimination campaign in Chicago and then visiting Marks, Mississippi, a tiny town in the Delta. After witnessing a teacher quarter an apple to feed four hungry students, King uncharacteristically broke into tears and told his chief lieutenant Rev. Ralph David Abernathy, “I can’t get those children out of my mind . . . We’ve got to do something for them . . . We can’t let that kind of poverty exist in this country.” NAACP attorney and long-time friend, Marian Wright Edelman, having led U.S. politicians on poverty tours through the South that summer, persuaded King to embrace former U.S. Attorney General Robert Kennedy’s suggestion to “’bring the poor people to Washington.” And with that, the Poor People’s Campaign (PPC) was born.

During the tumultuous summer of 1968, a racially, geographically, and politically diverse group of over 3,000 poor people and their allies traveled in nine regional caravans to the nation’s capital where they built a temporary city on the National Mall. Participants lived for six weeks in small, wooden, A-frame structures in their shantytown dubbed Resurrection City. They organized daily protests at a wide range of government offices to advocate for the multiracial poor’s diverse needs, presenting government officials with a long list of evolving demands. Yet the PPC consistently fought for guaranteed jobs or income—a common demand that spanned the spectrum of Black Freedom Struggle activists, from A. Philip Randolph and Bayard Rustin’s “Freedom Budget” to the Black Panther Party’s “10-Point Platform.” The mainstream media and far too many scholars have habitually ignored or maligned the PPC as King’s “last crusade,” but more recently, its lasting influence has gained increased recognition.

There was a follow up to the 1968 Poor People's Campaign that included the establishment of a Poor People's Embassy and an attempt to repeat the Campaign in 1969. Marian Wright Edelman founded the Children’s Defense Fund in 1973 and has remained the nation’s fiercest anti-poverty activist and lobbyist. The Poor People's Economic Human Rights Campaign (PPEHRC) formed in 1998 and has led campaigns on the PPC’s anniversaries and at national political conventions. More recently, in 2011, Cornel West and Tavis Smiley led “The Poverty Tour: A Call to Conscience,” and there is evidence that Dr. King’s final campaign inspired the original call that led to the Occupy Wall Street movement.

Despite these efforts, poverty and economic inequality top the civil rights movement's list of “unfinished business.” While the poverty rate dropped from its first estimate in 1959 at 22.4% to a low of 11.1% in 1973, it has since risen, topping 15% during the mid-1980s, mid-1990s, and in 2010 in the wake of the Great Recession. U.S. Census data from 2015 reported a poverty rate of 13.5%, with a total of “43.1 million poor people." What's more, one in three impoverished people were children, fully 20 percent of all children living in American. Despite these deeply troubling statistics, the Children’s Defense Fund reports that the Trump Administration’s 2017 proposed budget “Slashes $610 billion over ten years from Medicaid”; “Rips $5.7 billion from CHIP (Children’s Health Insurance Program)”; “Snatches food out of the mouths and stomachs of hungry children by slicing $193 billion over ten years from the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP)”; “Chops $22 billion over ten years from TANF (Temporary Assistance for Needy Families Program)”; “Whacks $72 billion over ten years from the Supplemental Security Income Program (SSI)”; and much more that will hurt our nation’s poor. In response, Rev. William J. Barber II, a leader in North Carolina's Moral Monday crusade, called for “a new Poor People’s Campaign for Moral Revival to help us become the nation we’ve not yet been.” While there are a myriad of issues facing the nation, the question remains, will King’s dream continue to be deferred, or will we truly tackle the issue of persistent poverty in a nation of plenty?

About Amy Wright

Amy Nathan Wright is an Assistant Professor in the School of Humanities at St. Edward’s University in Austin, Texas, where she teaches the Literature of the Black Freedom Struggle, as well as other interdisciplinary social justice courses on the history of marginalized groups and on contemporary social problems and issues of identity in the United States. She earned a BA in English as well as an MA and Ph.D. in American Studies from the University of Texas at Austin. Dr. Wright is currently completing her manuscript, “The Dream Deferred: Poverty, Race, and the 1968 Poor People’s Campaign.”

Amy Nathan Wright is an Assistant Professor in the School of Humanities at St. Edward’s University in Austin, Texas, where she teaches the Literature of the Black Freedom Struggle, as well as other interdisciplinary social justice courses on the history of marginalized groups and on contemporary social problems and issues of identity in the United States. She earned a BA in English as well as an MA and Ph.D. in American Studies from the University of Texas at Austin. Dr. Wright is currently completing her manuscript, “The Dream Deferred: Poverty, Race, and the 1968 Poor People’s Campaign.”