Fifty-nine years ago, the Freedom Rides of 1961 entered the state of Alabama. Potential violence awaited in Anniston and Birmingham. Below, the backstory of how the Freedom Rides began and how one of the most pivotal protests in the Civil Rights Movement came about. While we know the names of notable activists like James Lawson and Diane Nash, there are numerous overlooked details behind the scenes of this epic event.

The Freedom Riders story began fifteen years earlier in 1946 when Irene Morgan, an African American woman was arrested for opposing segregation in interstate travel. She took her case to the United States Supreme Court and won. The following year, the first Freedom Ride, then known as the Journey of Reconciliation, tested the Supreme Court ruling but gained little coverage. James Farmer and the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) decided to begin the Freedom Rides again to test the fourteen-year-old case when President John F. Kennedy was elected President in 1960. Civil Rights organizations wanted to see if the new administration would enforce the federal laws in the south. The Freedom Rides were set to begin with thirteen CORE activists in Washington D.C. on May 4, 1961 and their goal was to reach New Orleans on May 17, which would have been the seven-year anniversary of the Brown V. Board of Education ruling.

The Freedom Riders faced little resistance in the Upper South. However, when two buses arrived in Atlanta on May 14 and departed for Birmingham Alabama, history changed forever.

FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover, a known opponent of the Civil Rights Movement, informed the Birmingham Police Commissioner of Public Safety Eugene “Bull” Connor of the itinerary of the Freedom Riders arriving in the city. At the time it was viewed as a warning to Connor, but today, we see it as a tip to incite violence upon the Freedom Riders.

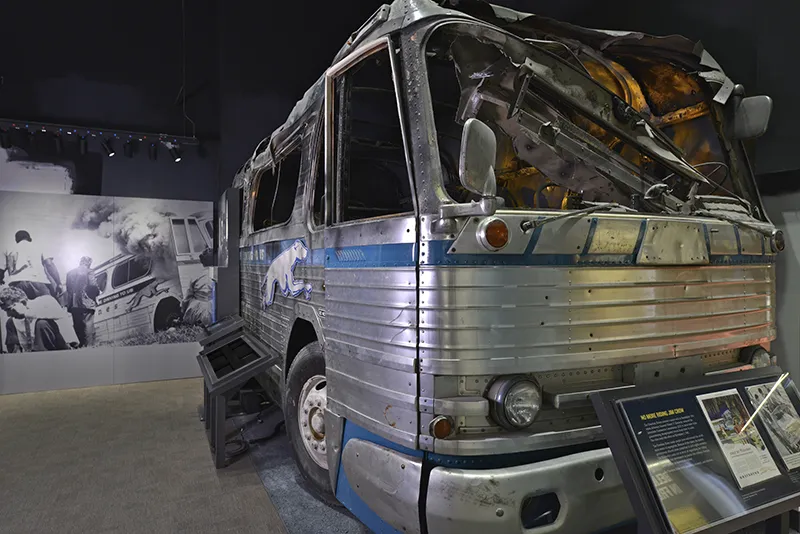

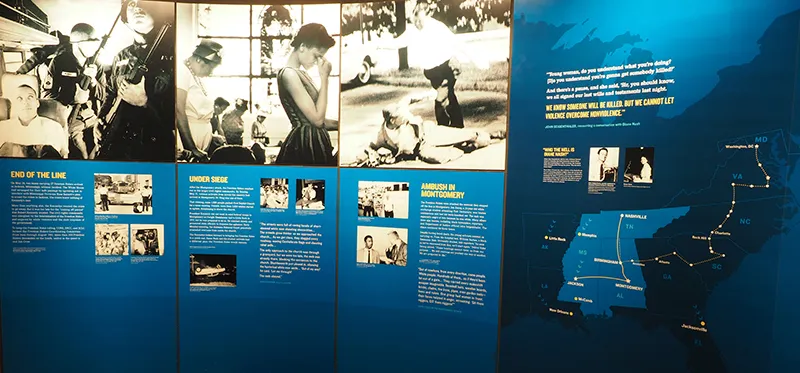

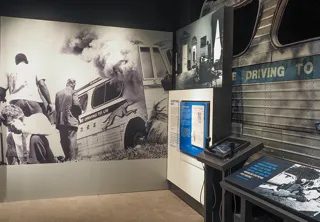

Bull Connor called the Imperial Wizard of the Alabama Ku Klux Klan and guaranteed them fifteen minutes alone with the Freedom Riders with no police. The first bus of Freedom Riders, a Trailways, did not make it to Birmingham. They are attacked in Anniston, Alabama, and the bus was firebombed by a white mob. The Greyhound bus riders arrived in Birmingham unaware of the attack on the first bus. Klansmen beat the Freedom Riders as Bull Connor promised to where more than half of them were hospitalized.

Bull Connor called the Imperial Wizard of the Alabama Ku Klux Klan and guaranteed them fifteen minutes alone with the Freedom Riders with no police. The first bus of Freedom Riders, a Trailways, did not make it to Birmingham. They are attacked in Anniston, Alabama, and the bus was firebombed by a white mob. The Greyhound bus riders arrived in Birmingham unaware of the attack on the first bus. Klansmen beat the Freedom Riders as Bull Connor promised to where more than half of them were hospitalized.

The entire world watched in anguish at the violence that took place in Alabama. The Kennedy Administration was concerned and asked for a cooling off period. Diane Nash of SNCC responded that “despite the violence, the Freedom Ride must continue.” The destination was Mississippi.

Kennedy called Mississippi Governor Ross Barnett to strike a deal behind the scenes unbeknownst to the public. Instead of ordering the Governor to enforce the federal law integrating interstate travel, Mississippi authorities agreed that there would be no violence and no mob, but would arrest and transport the Freedom Riders once they arrived at the terminal in Jackson, Mississippi.

Days later, the riders were convicted and sent to the Mississippi State Penitentiary, known as Parchman in the heart of the Mississippi Delta. The Parchman Prison Farm was one of the most notorious prisons in America dating back to the beginning of the 20th century.

Days later, the riders were convicted and sent to the Mississippi State Penitentiary, known as Parchman in the heart of the Mississippi Delta. The Parchman Prison Farm was one of the most notorious prisons in America dating back to the beginning of the 20th century.

Governor Barnett would privately say, “We don’t want to break their bones. We only want to break their spirits.”

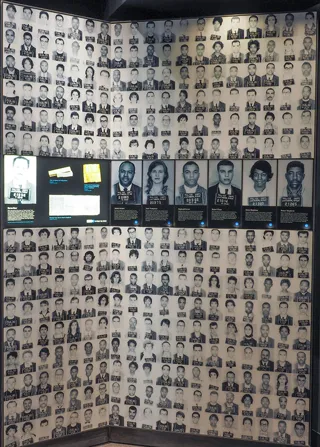

The Freedom Riders at Parchman experienced psychological torture for up to sixty days at a time. They were sent off to chain gangs, beaten by prison guards, and were forced to live under extreme inhumane conditions. Some Freedom Riders would be placed in a cells only a few feet away from the execution chamber on death row. As barbaric as Parchman was, hundreds of volunteers still took the Freedom Ride and were sent to Parchman. By July 1961, more than 300 Freedom Riders were incarcerated at one time.

The Freedom Rides were the first nationally known interracial civil rights demonstration in the South. As more and more volunteers took the Freedom Ride into the South, the Kennedy Administration slowly evolved into an ally for the Civil Rights Movement. Later that year, Attorney General Robert F. Kennedy appealed to the Interstate Commerce Commission and filed a petition to end segregation in interstate travel. It was declared unconstitutional on November 1, 1961.

The Freedom Riders were victorious. The legacies of the Freedom Riders changed the world and inspired others to end racial discrimination in public life and will never be forgotten.

John Lewis would become a member of the U.S. House of Representatives and a Presidential Medal of Freedom recipient. Joan Trumpauer Mulholland would receive the National Civil Rights Museum Freedom Award and Wyatt Tee Walker would go on to become a high-ranking member of the SCLC and be responsible as one of the architects behind the Albany and Birmingham campaigns. Today we continue to preserve the stories, commemorate the events, and continue the journey for reconciliation for the ideals of freedom and justice for all citizens across the globe.

Stay tuned for our next blog next week documenting the profiles of unsung Freedom Rider participants. Also, visit our social media channels @ncrmuseum for profiles of more courageous Freedom Riders.

Arsenault, Raymond. Freedom Riders: 1961 and the Struggle for Racial Justice. Oxford University Press, 2007.